Join Us

Are you ready to join our global project support team?

IEEE Smart Village is looking for experienced volunteers and professionals who not only have a deep passion for humanitarian work, but also the expertise, experience, wisdom, and time to commit in support of our program. The primary role of our volunteers is providing pro-bono consulting, in-field technical & business support, and assistance with program organization.

We are currently seeking candidates for positions in our committees and working groups which typically meet online every two weeks. We are particularly looking to engage people with experience in sustainable development or participation in other IEEE committees to form and actively direct working groups within our education, engagement, fundraising, marketing, and technology committees.

Unlike many other IEEE activities, it is not necessary to be an electrical engineer or a member of IEEE to volunteer for IEEE Smart Village. We are eagerly seeking business analysts, education experts, marketing strategists, and sustainable development specialists in addition to engineers, technologists, and hands-on practitioners living in the field.

If you are a student or are interested in pursuing a small local project, we strongly recommend that you join or form an IEEE SIGHT group, which only requires 6 members. For more information, please visit http://sight.ieee.org/get-involved/. It is typically very challenging for students to maintain the regular weekly and monthly time commitment necessary to participate in IEEE committees and working groups.

We hope you are up for some dedicated and challenging work to help build skills and prosperity for some of the poorest people on the planet! It is an exciting opportunity to reach thousands (maybe millions of people) with the possibility to travel to places you never dreamed you would go (such as the Maa Tribes in Kenya, a monastery in the Himalayas at 5000 m, or the Galapagos islands).

To volunteer with IEEE Smart Village, please review and apply for one of our open committee positions in the “Volunteer” tab.

Are you a match for our global mission?

It is important to understand that IEEE Smart Village is not a charity. Instead, we function as a donor-funded venture philanthropy group seeking to launch holistically sustainable social businesses (both for-profit and NGO).

Our emphasis is the long-term financial sustainability of large projects that demonstrate the potential to scale with the eventual goal of providing economic empowerment to a million people in 10 years.

Please not that if your project is focused on technology development and small-scale deployment rather than regional expansion, there are additional support resources available through other IEEE Humanitarian & Philanthropic programs:

- IEEE SIGHT (http://sight.ieee.org/): Funding under $20,000 USD for small projects and student groups. Projects should involve local volunteers with a minimum of 6 IEEE members or student members. Funding is provided through the SIGHT group.

- IEEE HAC (https://www.ieee.org/about/corporate/humanitarian-activities-committee.html): Funding between $20,000 and $60,000 USD for technology deployment projects in at-risk communities with participation of local IEEE members. Funding is provided through the local IEEE chapter, society chapter, or section.

- IEEE Smart Village: Funding between $50,000 and $200,000 USD for regional programs with a focus on electrification, education, and creation of holistically sustainable business. Applicants should be startups or well-established NGO with staff. Funding is provided directly to the applicant through a Project Agreement contract.

We recognize that electricity is usually one of many needs, but by itself is not enough to build a “Smart Village.” We desire that projects systematically address all three pillars – electrification, education, and entrepreneurship. Education (including technical, K-12, and vocational training programs) is the catalyst to empower the next generation of any community. Entrepreneurship focuses on creation of jobs and economic opportunities through access to technology and vocational training. In summary, the IEEE Smart Village model is a sustainable reallocation of commerce that creates value for its communities enables them to become self-sufficient, instead of dependent on foreign gifts and grants.

We acknowledge and respect that there are many approaches to developing communities, but our team prefers to partner with experienced organizations with proven processes that align with our own goals. For the sake of better understanding our requirements, we’ve created ten points that summarize what we value in our global partners:

- Understands and embraces ISV’s three pillars: Electricity, Education and Enterprise

- Startup experience with demonstrated success

- Respectful relationships which view communities as working partners, not charity cases

- Respectful relationships with authorities at the village, state and national levels

- Excellent management team with business, technology, and education components

- Clear vision of a business plan capable of reaching at least a million people

- Ability to attract investment capital for growth after a successful pilot

- Ownership plan that includes and incentivizes community members as business partners

- Willingness to collaborate with holistic partners in addressing other critical needs

- Passion and dedication to tackle the daunting challenges along the way

If your organization embraces these principles, we’d like to learn more about your thoughts on these points, the team that you work with, and how they are making a difference in their communities. Our goal is to launch ten new partnership startups every year for a decade – we will need the support of like-minded organizations to make that happen. We look forward to learning more about your organization so that we can share knowledge and develop ways to support each other.

To get started, see the “Apply for Funding” tab on this page to learn about next steps and our application process.

In the words of our own entrepreneurs, learn how your support and contributions can improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of people worldwide.

Bai Blyden: Empowering Africa

“Worrying about Africa is the family business,” says Bai Blyden, an IEEE Smart Village Ambassador and Mentor whose life revolves around solving the energy needs of this vast continent.

More

Blyden grew up rooted in the legacy of his great grandfather, human rights advocate and political philosopher Edward Wilmot Blyden, considered by many to be the Father of Pan Africanism, and that of his father, Edward Blyden III, who played a key role in winning Sierra Leone’s independence from Great Britain.

The elder Blyden, who devoted his life to “uplifting the lives of black people” and whose work in the mid-to-late 1800s inspired African consciousness movements all over the world, passed on to his grandson and his great grandchildren a legacy of putting “others before self.” So powerful was his influence that Bai and his seven siblings all embrace a commitment to social change as part of their own life’s work.

“Every one of us has a different discipline,” he says, including engineering, history, geology, biology, social activism and journalism. “But wanting to give back, we all inherited that.”

“Yet there was never any real pressure on us to excel,” he explains. “My father was not that kind of a teacher.” Rather, Edward III exposed the family to many cultures and societies through their travels (they lived in the U.S., Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Russia during his youth) and encouraged open discussion of a wide range of religious and cultural beliefs and ideas. “We talk about everything in our family,” Bai says.

Bai remembers his father driving him around many poor villages in Nigeria, where people’s only source of water was what they could carry on their heads. “There but for the grace of God go I,” he used to think, voicing a family mantra no doubt first invoked by his great grandfather, who was born a free black man on St. Thomas, Virgin Islands at a time when so many were enslaved.

Bai was taught to regard others — all others — as his equals. Consequently, he developed a strong belief that anything he had in life, be it a pair of shoes or an education, should be equally accessible to all.

From the age of three, Bai also developed a deep love and admiration for anything that had to do with dynamics, starting with airplanes and quickly expanding to include Batman and the astronaut Buzz Aldrin as heroes. “I actually took Batman seriously,” he says now, reflecting back on his childhood. “He was the more believable one of all the superheroes. He didn’t fly. He was an engineer.” By the time I was 14 I had grown to like physics and had inscribed in my physics book Buzz Aldrin and Bai Blyden Ph.D, MIT, that’s how much he inspired me and continues to inspire others even today. His outreach for example to the Hip Hop community and Wakanda generation in a Rap video is quite noble and Black Panther and Ron Mcnair like Batman and Buzz Aldrin for me can certainly further his outreach”.

Bai would become one as well, studying Power Engineering at the Moscow Energetics Institute, where he specialized in Power Generation , Power Systems and Industrial Distribution systems Design , graduating with a master’s degree in 1979.

“Power is the most transformative form of energy there is,” he says. “There’s a great need for it. I was advised by the rector of the Institute, who said, ‘If you stay with design, you’ll always be useful. Not everyone can do that.’”

That advice resonated strongly with Bai, whose desire to serve others, passion for engineering and legacy of devotion to improving the lives of people in Africa dovetailed into what would become a lifelong focus on how to most effectively bring electric power to developing nations.

“The last century has demonstrated that every facet of human development is woven around a sound and stable energy supply regime,” he wrote in a paper for the IEEE Power & Energy magazine in 2005, in which he outlined efforts by the African Union (AU) and New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) to develop an integrated African grid. “Indeed, electricity is the engine of economic growth and development,” he wrote, noting that the overwhelming majority of the population is not connected to any grid, or form of electricity a major contributing factor to the continent’s underdevelopment.

Bai, today a Senior member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) has worked on more than 40 major and minor power plant projects from design thru construction throughout his career, and has been published widely in international, peer-reviewed journals. He has done extensive research “in the African energy space,” developing a model known as the Knowledge Engine, which focuses on accelerated development and knowledge transfer, particularly in the power and energy field.

“One of the outcomes of my research in the African energy space was the realization that there was a need for accelerating training skills and knowledge transfer, as we are very much in the information age,” he says. The Knowledge Engine recognizes the need for a standardized curriculum at it’s core and establishing online and local communities of experts in the needed fields to share knowledge among universities and technical schools in Africa and between Africa and the rest of the world., This strategic collaboration would allow local people to obtain the training they need to accelerate the development of renewable energy micro grids and regional power pools, now in the nascent stage.

Such groupings of skilled technologists and other supporting disciplines, says Bai, would function like “energy Peace Corps” in Africa, bringing much-needed power to remote villages now dependent on kerosene and candles. He has been promoting the model to celebrity philanthropists with an interest in global development and had begun discussions with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy to explore the possibility of using it in conjunction with the Obama administration’s Power Africa program and Global Connect initiative.

For years, Bai’s research and interest in the development of an integrated energy grid in Africa was focused at the macro level. But about nine years ago, he ran into a group doing work at the micro-realization level in Africa that set off light bulbs in his head.

At the 2011 inaugural Global Humanitarian Technology Conference in Seattle, hosted by the IEEE Foundation and the United Nations, Bai met representatives from IEEE’s Smart Village program. Smart Village provides innovative, sustainable electrical systems and start-up training and support to energy-deprived communities in the poorest nations of the world. For example, their very basic technology solution can provide LED lights bulbs and battery packs with solar voltaic chargers to families so they can charge cell phones and provide lighting for children to do their homework at night, replacing dangerous kerosene lamps that cause health problems.

At first, Bai was skeptical. He thought, “Here we go again, people thinking they can solve Africa’s problems with a project. I was used to thinking bigger than that, about things like combined cycle gas turbine plants, nuclear, small to large hydro power plants and micro grids in the megawatts. Then I saw the heart that went behind the concept, of going after the most deprived and really making a difference in his life with the bare minimum of empowering technologies. Their idea of reaching out to the most disadvantaged around the world using electricity, education and communications to empower people really resonated with me and was philosophically in sync with much of what I’ve been writing about for the past 35 years.”

IEEE Smart Village, he realized, was his “energy Peace Corps” in action.

So Bai joined the IEEE Smart Village Steering Committee and now serves as a Smart Village Ambassador and Mentor. His role is to identify where opportunities exist, finding the villages and towns that most need energy assistance. He provides technical direction and assistance with fundraising as well.

What’s next for a man whose life’s goal is to see Africa fully energized? He’d like to see the Knowledge Engine “turned on,” incorporating his model into the work being done by the likes of USAID Power Africa, ADB’s PIDA program, The Global Connect Initiative, Smart Village and other related programs. Their strategic collaboration in , working with universities and technical schools as detailed in the Knowledge Engine can develop the 21st century entrepreneurs and technologists needed to carry this work to fruition.

Learn more about how you can support IEEE Smart Village by becoming a volunteer or a donor.

Mou Riiny

My exodus from South Sudan as a boy amid war and my chance to return as a man to help my countrymen has been a journey of a lifetime, and I am still a young man.

The IEEE Smart Village Initiative – meaning, the people who make it the positive force that it is – has played a significant role in my ability to bring a change to my former village of Thiou in South Sudan. I’d like to tell that part of my story.

More

Sudan was torn apart by civil war in the 1970s and again in the 1980s. In the latter conflict, tens of thousands of boys, including me, fled the war and possible conscription as combatants. We walked hundreds of miles over months to reach crowded refugee camps in neighboring Kenya. Half of my compatriots died along the way. The survivors remained there for years. In 2000, the U.S. State Department relocated perhaps 4,000 of us to the U.S. and I grew up in foster families in Massachusetts.

Guided by a teacher, I studied math and engineering, eventually becoming a student at the University of San Diego (USD), where I graduated with an electrical engineering degree in 2011 – the same year that South Sudan became recognized as its own country.

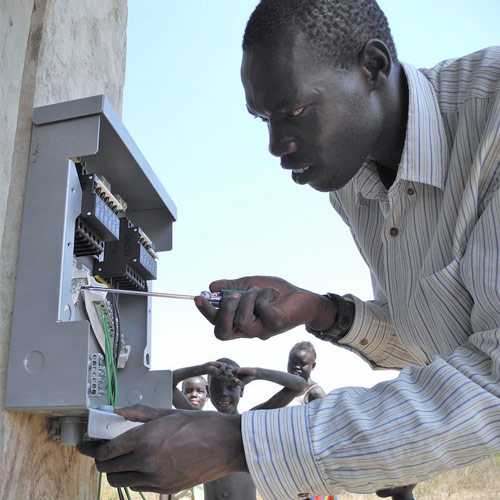

By then I’d met Ron Moulton, director of a group known as Village Help for South Sudan, and learned of something called the Thiou Village Project. As part of a senior project at USD, I traveled with several American classmates to Thiou to install solar panels, inverters and provide battery packs that could recharge portable batteries to power lights, radios, laptops and other portable electronic devices. My old school was the first project. People actually walked for miles to see me to turn on the first lights ever seen in Thiou!

This work led me to attend several international conferences, where I met other people working on similar goals. In 2011 I attended the first IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC) in Seattle. In 2012, at the Power Africa conference in Johannesburg, I met many people affiliated with the IEEE Community Solutions Initiative (CSI), including Ray Larsen, Mike Wilson, Martin Niboh and Patrick Lee, and they introduced me to the CSI’s entrepreneur-based business model. I returned to Seattle for the second IEEE GHTC, where I met Robin Podmore, who also expressed interest in my background and the work we were doing in Thiou.

Having completed the initial work in Thiou with support from the Village Help for South Sudan Project, I presented a paper, “South Sudan Rural Electrification Project,” at IEEE’s 2013 Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC) in San Jose, Calif. The entire group of volunteers encouraged me to adopt its entrepreneur-based business model. This led to further work for me in South Sudan, but as an entrepreneur.

Under that model, I formed a company called SunGate and we are now working in three states in South Sudan, one of which includes my original home in Thiou. We are building solar charging stations and distributing battery packs to those who need them. At this point, we have provided nearly 1,000 battery packs to homes with maybe six people each, so we’ve affected change for nearly 10,000 people. At first, of course, many people did not even realize what electricity is or can do. In Juba, the capital of South Sudan, only a fraction of the people has electricity for a few hours each day. Outside the city limits there is no grid. So it takes time for villagers to grasp the benefits, but as many are getting radios and cell phones, they get it.

Now we are introducing these innovative systems, and their excitement is overwhelming. They have a saying there that “we should bring the town to the people, not the people to the town,” so bringing electricity to them with a solar home kit, for instance, makes their home into a town. Many villagers want to rent a portable battery for their home so their children can read at night, but others are taking them to more remote villages to charge $1 for cell phone charging and they can make perhaps $150 per month, as long as they return to us to charge the batteries.

When I was growing up in Thiou, very few of us went to school. Today, most children go to school. So at night, the mother has light to cook by, the father and the children can read, and it has a bit of status to it – having a lit home. Education will be improved this way, and side businesses are made possible.

In the future, well, these people already know about refrigerators and televisions and they’ve asked whether we can power them. And I say “Well, it’s coming down the line. No problem. Let’s get this working, and we’ll bring the next-generation renewable-energy technology.” So they’re already asking. But we have a bottleneck. The solar technology we need is not available in South Sudan. The traditional means has been diesel-powered generators, which are noisy, dirty, expensive and they break down.

Solar-based electricity is a great solution. Kerosene makes poor light and it’s dirty. I’m confident we can scale up what we’re doing to help reach the IEEE Smart Village goal of 50 million people in 10 years. Personally, I can say “thank you.” All this would not have been possible if Robin had not contacted me and pulled me into the Smart Village project. I have been able to find other opportunities elsewhere because IEEE introduced me to the innovative business model and system design for bringing electricity to energy-poor people. We took it and we ran with it, and so I give thanks to IEEE.

Learn more about how you can support IEEE Smart Village by becoming a volunteer or a donor.

Marias Ripau

I was born and brought up in a small Maasai homestead in the rural County of Kajiado, Kenya. A prominate image of my childhood is darkness and flickering light because we had no electricity and I depended on kerosene-lit lamps to do my homework at night. Despite these challenges, I was so determined to finish my primary school and thankfully I was one of the few students in my home area who proceeded to secondary school, a mythical place that my English teacher had told me about.

More

The lack of sufficient lights affected my studies and eventually I visited an optician who told me that I needed glasses. I looked very funny with oversized glasses and my classmates nicknamed me “Daktari”, which means doctor in Swahili. Although it was a jest, this nickname actually inspired me to work hard. I knew first-hand the consequences that the lack of lighting, and at the back of my mind, I developed a desire to provide better lighting for my rural school. After finishing my secondary education, I formed a group that advocated for ‘’TAA YA HOMEWORK’’ (meaning, a light for homework). We mobilized funding and bought pressure lamps for the school and because of these lights, the school was able to start evening tuition classes for all pupils to do their homework. Over the years, through this initiative, and in collaboration with other stakeholders, all schools in my locality have received solar panels. Lights are no longer a problem in schools, but they remain a big challenge at the household level.

This is where my passion is. Identifying a problem and in a small way effecting a solution. The IEEE Smart Village program has helped me share my story and personal journey of transformation from a dark village in a rural county in Kenya to the best national secondary school and later University. A story of a village boy that darkness did not derail his ambition to acquire education and help his community.

In my role at The Maa Trust, overseeing all enterprise activities, I have repeatedly witnessed the great power that this grassroots approach to development can have upon individuals, families and wider communities. Maasai people do not want to be given free aid, they want the opportunity to develop the skills that they need to earn an income, support their families and improve their lives. Combining social enterprises with sustainable technologies is an innovative, yet very successful partnership. Empowering individuals to earn money and then educating them how to utilise this newfound income in a way that will address their most pressing needs is an essential, yet rarely implemented, activity.

With this first-hand experience of its potential, I am passionate about the three-pillared development entry point which combines entrepreneurship, education and technology. Having seen for myself the powerful impact that this can have upon poor Maasai families, I am excited to see how The Maa Trust can work together with IEEE Smart Village to further this objective for the benefit of thousands, and potentially millions of rural Africans.

Learn more about how you can support IEEE Smart Village by becoming a volunteer or a donor.

Robin Podmore

Growing up on a small farming town in New Zealand with a passion for building things, I knew I wanted to become an engineer. But it wasn’t until I selected modeling power system networks at University of Canterbury, Christchurch for my Ph.D. studies I that I was introduced to the IEEE Power and Energy Society (PES). Thanks to this connection, the Power Apparatus and Systems journal and the Power Industry Computer Application (PICA) Conference Proceedings became my lifeline to the rest of the power engineering world. I wrote to the authors of PES journals, which brought me to the University of Saskatchewan on a post-doctoral fellowship.

More

My early mentors shaped my future in ways I couldn’t have predicted and IEEE has been my family away from New Zealand ever since. In retrospect, I’m very grateful for those mentors who helped me along the way. As I pursued my Ph.D., I was fortunate to work with Dr. John Undrill another fellow “Kiwi” and graduate of University of Canterbury. During your Ph.D. it can feel as though you are wandering in the wilderness without a compass, and the competitive nature of Ph.D. programs only exacerbates the stress. I was fortunate to have such a strong mentor at this formative stage in my life and career – and as a result, settled on a practical set of computer network analysis problems for completing my thesis. Dr. Undrill subsequently pioneered some of the major power grid simulation programs used by the industry today – and had it not been for this relationship, I may very well have missed an entry point into the electric power engineering field.

Ever since, mentorship has been a constant presence throughout my career. I’ve been on both sides of the ledger – as a mentee and a mentor – but I never stay on one side for very long. Through many transitions, from student to professional, from entrepreneur to volunteer, I’ve realized that mentorship is cyclical and the roles are fluid. By committing to share knowledge with others, and accepting wisdom in return, mentor relationships can flourish in unexpected places.

While I was confident as a newly-graduated Ph.D., I knew that I still had much to learn from other mentors. I continued to seek out luminaries in the field, which led to a meeting with Dr. Neal Stanton and Mr. Norris Peterson at the 1973 PICA Conference in Minneapolis. Neal offered me a position with Systems Control in Palo Alto the next year.

These mentors shaped me beyond academics. They taught me aspects of their business, and I learned how to apply core values – hard work, honesty and integrity – to a business setting. This relationship flourished, and in 1979 we launched Energy Systems Computer Applications (ESCA). This grew into the world’s largest supplier of Energy Management and Market Management Systems and was recently acquired by General Electric Corporation.

In 1990 I launched Incremental Systems Corporation (IncSys). IncSys and PowerData have focused on training power system operators world-wide with a highly realistic power system simulator. This has led to training assignments in Iraq, Jordan, Ireland, Brazil and Kenya as well as throughout North America. Our Power4Vets program with the IncSys Academy has recruited, trained and placed over 200 US Military Veterans as power system operators throughout North America. The IncSys Academy uses an on-line Digital Virtual Instructor and has been one of the most satisfying outcomes of our work. We are now applying the Digital Virtual Instructor to capture and transfer knowledge in Smart Villages.

Despite this successful foray into the business world, I continued to value my mentors as much as ever – and actively sought out more. PES helped me connect with my most recent and impactful mentor Ray Larsen, Co-founder and Chair of IEEE Smart Village.

By now, it’s clear that I’ve benefitted from good mentors on a professional level. But I’ve been careful not to compartmentalize opportunities to learn. My personal experiences have presented many lessons which I’ve applied to my work as well. My son’s experiences in training as a helicopter pilot first in the US Marine Corps and now the U.S. Coast Guard taught me much about leadership and serving others first. I admire their camaraderie and dedication, and I’ve worked to instill this ethos within IEEE Smart Village.

At its core, IEEE Smart Village works to foster mentorship-based relationships all around the world. By drawing on the IEEE extended family, we’re bringing together specialists from all walks of life, each contributing their own experiences and best practices. As a result of this teamwork, all involved are better off. Most importantly, the circle of mentorship extends to our partners in the field, who reciprocate with even greater insights as we share with them. Working across oceans and cultures, the grassroots models our partners use to cultivate teamwork, work efficiently, and utilize relationships with people of excellence, in local government, academia, and industry to transform lives in their communities reveals many lessons for the future.

As a mentor myself, I take care to convey a few core principles: the importance of a clear mission, described with passion that inspires others to help make it a reality. I am forever learning to be a good listener, creatively solve problems, manage conflicts, and balance my weaknesses with others’ strengths. I’ve also learned that fostering fruitful mentor relationships across nations and cultures — as IEEE Smart Village’s work does every day — takes patience. These skills will serve everyone in a mentoring role well, no matter the context.

The true heroes and mentors of IEEE Smart Village are our entrepreneurs working in the field, such as Mou Riiny (South Sudan), Ifeanyi Orajaka (Nigeria), Martin Niboh (Cameroon), Jude Number (Cameroon), Likonge Makai (Zambia) and Paras Loomba (Ladakh, India) who have led the way and are now mentoring our next generation of Smart Village Entrepreneurs. I am especially grateful to my wife and co-business owner Stella Podmore and all the employees at IncSys and PowerData for their support along the way.

Mentorship only flourishes when there are positive motivations for getting involved. At its core, our work is humanitarian – and the way we’re helping people is by making real connections. We’re not tourists or charity workers; rather, we’re laying the groundwork for enduring relationships that enable transformational change. I’ve come a long way from the farming town in New Zealand, and this journey has been a success because of the mentors I’ve encountered along the way. Ultimately, these connections make all the difference.

Learn more about how you can support IEEE Smart Village by becoming a volunteer or a donor.

Ifeanyi Orajaka

From the pilot projects we have deployed, our business model has proven sustainable and scalable. Our fee structure is designed to give customers the best service at the lowest possible rate, making off-grid electricity provision reliable and affordable. Our ultimate goal, with the Bank of Industry’s financing and the support of IEEE Smart Village, is to light 200,000 homes to serve a million people over the next five years.

More

This ambitious plan will sustain GVE Projects, Ltd., if all goes well. One of our major drivers has been the satisfaction we take in creating value and the socio-economic uplift in the lives of the indigenes of our host communities. We are agents of change, for the common good. I asked one of my customers to describe the impact of reliable, affordable electricity on his life. How did he light his home at night? How did he charge cell phone batteries?

He told us:

“Before now, we relied on basic local means like kerosene lanterns, candles and, at rare times, ‘I pass my neighbor’ generators to provide light. Normally, we would go to the village market center to pay and charge our phones. Since GVE came in, these are struggles of the past.

“Before now, I spent about 450 naira (about $2.25 USD) daily for three liters of fuel, but now I spend about 200 naira for better value. I have longer hours of electricity, without generator noise and fumes. My children can read in the evening, after school. I do not travel to charge my cell phone, which allows me to spend more business hours at my shop. The benefits are so many to count. Compared to how much I spent on fuel and alternative sources before GVE came to our community, the service is really affordable.”

Our business and the positive impacts we’re having on off-grid communities in Nigeria has been made possible through my own membership and participation in IEEE and the support we have received from the Smart Village Initiative. My colleagues and I are grateful for IEEE’s support, which began when we were merely young students with lofty ideas for an energy access revolution in West Africa. And we are honored to be ambassadors for IEEE wherever we go.

I joined IEEE in 2009 as a student member and had the good fortune to lead a team that won an Outstanding Student Humanitarian Prize in the inaugural IEEE Presidents’ Change the World Competition that year for our “Project Spread the Light: Provide Electricity in a Small Settlement.” IEEE Executive Director Jim Prendergast personally alerted me to the Humanitarian Technology Network, which I joined, as it meshed with the objectives of my team’s project.

This led me to join the Community Solutions Initiative, which became today’s IEEE Smart Village Initiative, and to present papers at international IEEE conferences, including regular attendance at the annual IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference.

IEEE’s support provided me with credibility and led to collaboration with other organizations, such as the U.S.’s African Development Foundation that sponsors the Power Africa Off-Grid Energy Challenge. Upon an invitation from the U.S. Department of State I attended the 2015 Global Entrepreneurship Summit in Nairobi, Kenya.

All of these factors contributed to the success of GVE and the credibility that GVE and its collaborators brought to our application to Nigeria’s Bank of Industry.

As with other start-ups, the process of establishing such a business has not always been rosy. We have encountered critical challenges, including severe financial constraints. We have made sacrifices. But the families we empower have been supportive and have bought into our dreams.

Now, on a daily basis, we are applying the electrical engineering education we learned at university as well as the experience we’ve earned through our field deployments, as well as through the support of IEEE PES, the IEEE Smart Village Initiative and the international conferences we have been enabled to attend. Today, GVE Projects, Ltd., has become one of the most well-known renewable energy providers in Nigeria.

Learn more about how you can support IEEE Smart Village by becoming a volunteer or a donor.

Avoki Omekanda

IEEE Smart Village Entrepreneur Avoki Omekanda remembers a time when the country he was born in offered a decent and affordable education, but it’s been decades since things have been that good in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), formerly Zaire.

More

“I was born right before the independence,” he says, “in 1957. But as time passed, life became miserable there. The university was closed for two years, 1979 and 1981, under the military dictatorship of President Mobutu Sese Seko.”

Avoki attended high school and the first two years of engineering school in the Congo before leaving to continue his education in Morocco for two years, and Belgium for 12 years, where he obtained his Engineer diploma and PhD in Electrical Engineering. “Things back home were not good then,” he remembers.

They still aren’t. Decades spent under Mobutu’s dictatorship followed by years of civil wars ravaged the country, claiming more than six million lives due to fighting and starvation.

Avoki returns three times each year to teach electrical engineering at a local university in the capital city of Kinshasa, where students will sit in the hot auditorium to hear him lecture sometimes as long as 10 hours, “just to hear something new in recent advances of science and engineering. They really appreciate that,” he marvels.

Taking time away from his job as a Research Engineer at General Motors R&D Center to teach in Kinshasa isn’t easy, but Avoki cobbles together weekends, holidays and vacation time to make it work because he wants these students to have as good an education as possible. “There is no internet, no library at their school. It’s miserable. The students will come any time I tell them to come. I show them videos and tell them the real engineering story,” he says. “I try to raise their hope by showing them, ‘I am one of you.’ I tell them, ‘Just work hard and keep grabbing whatever you can in life.’ They listen.”

He’d like to do even more. Through his position on IEEE-Industry Applications Society (IAS)’s Executive Board, Avoki learned about the Smart Village program, which provides innovative, sustainable electrical systems and start-up training and support to energy-deprived communities in the poorest nations of the world. “As soon as I showed an interest in this, the President of IEEE-IAS said, ‘This is great,’ and started to show me slides about what IEEE Smart Village was doing in Nigeria, Haiti, Namibia, Zambia, etc. But not DR Congo.”

Before he knew it, he was being asked to become Ambassador for Smart Village programs for all of Africa, Avoki says. That seemed too much, so he asked a Ghanaian colleague, Dave Kankam, who works at NASA to split the continent with him. “I asked him to take half of Africa and I took the other half, including Congo.”

He’s particularly interested in helping people in Sankuru, the region in which he grew up. “It’s about as big as the state of Michigan,” he says, “and they have zero electricity.”

Avoki is putting together a Development Program for Sankuru province of DR Congo, with the help of skills gained from a Masters’ Degree in Development Practice (MDP) taught online by Regis University, with support from the IEEE Smart Village.

“One of the things we learned is that engineers think that because they have a solution, that solution will work everywhere,” he says. “This is a mistake. Something that works in America might not work everywhere. They told us to be humble. Talk to these people. Find out what are their needs, come up and listen to them and get their feedback. Make sure what you want to implement there is sustainable.”

Following this advice, Avoki met with his colleague at the University in Congo, who also happens to be the governor of Sankuru. He asked him to connect him to NGOs and others in his province that could advise him on their most pressing needs.

“Whatever I do there needs to be sustainable. I don’t want to do this and then leave and everything collapses.”

Avoki understands the importance of creating solutions that can be sustained because he has seen firsthand what happens when a program is not sustainable. He laments that the educational systems put in place in the Congo by Belgium that were there during his youth are now gone. “Everything has collapsed,” he says. “There’s no library now, nothing. I know they used to have it – I was there. It was not sustained. It was a failure. You bring education and then you leave and everything collapses.”

Having a local administrative and political contact, such as the governor of Sankuru, could also help cut through any bureaucratic or other hurdles, he notes. “The surface area of DR Congo is equal to 2.3 million square kilometers, which is an equivalent of 2/3 of the European Union. So, starting our development work in a local region, such as Sankuru, will increase our chance of success in DR Congo.”

Through his contact, Avoki has been putting together a local team that recently met in Kinshasa to discuss Sankuru’s needs and make plans for a survey to be conducted in the near future. He learned that USAID has been donating medication to the region but there is no place to properly store it because there is no power to keep it cool. Another big need is for irrigation, which can be accomplished through solar-powered pumps. There is also a need for clean water. None of these things can be accomplished without electricity.

“There’s kind of a chain of things,” he says. “Our goal is electrification, but only electricity is not enough.”

Helping the people in his region of birth would be a dream come true for Avoki, who feels compelled to give back to a people and place that inspired him to become what he is today. “As I was growing up, math and science were easy for me,” he remembers. “I was first in my class, it came naturally to me, but I didn’t appreciate it. Then one day the principal of my high school came to me and he said, ‘Someone like you needs to go to a school of engineering.’ He even said, ‘I am going to do my best to get a scholarship for you,’ which he did. My family and friends encouraged me, too, because they said being an engineer is a hard thing, but for me it was easy.”

“So I decided to become an engineer, because I wanted to bring technology into people’s lives in DR Congo in order to make life better.”

One thing he wants to see happen quickly is to provide light in people’s homes so that children can do homework at night. “Darkness comes at 4 p.m.,” he says. “There aren’t even candles. Candles are a luxury. They have tree oil and a piece of cotton and you light it. The oil is very bad for your health.”

He also wants to focus on improving the educational system. “The state of schools in DR Congo needs special attention! They appear to lack everything.” He wants to start by running an assessment with his IEEE Smart Village colleagues to quantify the country’s needs and then identify local partners who can help bridge those gaps.

Working with the IEEE Smart Village, he says, has finally given him the opportunity to create substantial change. “The willingness to help people of DR Congo was always in me” he says. “But the opportunity created by the IEEE Smart Village initiative has been a vector and a platform that I can now use to make this dream real. It’s very time consuming, but very satisfying, to think that I can one day make a difference.”

Learn more about how you can support IEEE Smart Village by becoming a volunteer or a donor.

Niru P. Kumar

As I was finishing my MBA in the summer of 2013, I realized that my true interests were in renewable energy and social enterprise. However, I didn’t know how to marry the two interests. That is when I came across IEEE Smart Village. It was a perfect marriage of my two passionate interests and that is when I decided to volunteer for it.

More

My journey with IEEE SV began when Mike Wilson gave me the assignment of scanning all the Portable Battery Kit (PBK) manufactures in the world and coming up with not only a list of PBKs that would suit the IEEE SV SunBlazer product, but also requesting the manufacturers to send sample products to us. I ended up contacting more than 75 PBK manufacturers and more than two dozen of them sent me their PBK samples from around the world. Talking to so many manufacturers who were also deploying rural electrification solutions around the world changed me somewhere completely. I saw my world and my 24 hours of electricity based existence very different from then on.

I was soon invited to come to GHTC 2013 in San Jose, California, to meet the whole team and I have never looked back since.

In February of 2014, an opportunity came to talk at a conference in Harvard University’s business school. The chairs of IEEE SV, Ray Larsen and Robin Podmore and the Sr. Program Manager Mike Wilson asked me to represent the program and also gave me the title of an ‘Ambassador’ of the program, a title I have cherished since. Later that year I attended a UN conference on Gender and Energy Access as an Ambassador for IEEE SV. I had started some initial research and work on IEEE SV entering India, but soon got a full time job in Nextera Energy. A full time job did not stop me from participating in IEEE SV though. I continued to work with IEEE SV in different formats – helping our Zambia partner with initial business plan work, talking at the IEEE SV workshop at GHTC 2014 etc. Then in October 2014, Robin asked me to conduct my own panel on Sustainable Microgrids at the Intellect 2015 conference in Mumbai, India. The panel had some really young speakers and was a big success. Later in 2015, I conducted the very first IEEE SV Ambassador workshop in Denver, CO, an event part of the larger IEEE SV program at the 2015 IEEE PES General Meeting. In September 2015, I spoke at a conference in Bangalore, India.

At work I was given a ‘Volunteer Spotlight’ on our website for my work with IEEE SV. This led to a lot of enquiries about the program from my colleagues. The enquiries grew to such an exciting level that we now have a whole dedicated group of volunteers for IEEE SV projects. The group is starting some very exciting work and I can’t wait to see it grow more.

About my journey with IEEE SV, which started more than 5 years ago, I can only say that it is one I see continuing for a long time, till we reach the goal set out by the mission of electrifying 50 million people in the next 10 years and beyond that. I have also gained so much from this experience – so many contacts, so much exposure and many many friends. As I have always said – by giving my time and effort to IEEE Smart Village, I have always gained more than I have ever given.

Learn more about how you can support IEEE Smart Village by becoming a volunteer or a donor.

Are you ready to become an IEEE Smart Village Entrepreneur?

We have a phased process for applying for funding and becoming an ISV entrepreneur, which typically takes 12 to 18 months from initial outreach to execution of a project agreement.

1) Identify the Applicant Organization: This could be yourself, a local startup, or a qualified NGO with an extensive boot-on-the-ground presence that is ready to expand to a regional scale. Our program is structured to bring benefits and employment to communities and to educate local people to manage all the technical and business aspects of the local operation. Our goal is holistically sustainable economic empowerment, not charity.

2) Conduct Detailed Community Surveys: Having a strong local team is important, but so is understanding the needs, desires, dreams, existing competition, and potential opportunities in your target communities. This can only be done with detailed studies examining factors including current access to energy, education, water, sanitation, and opportunities for creating jobs in technology, IT outsourcing, agriculture, artisan crafts, construction, and numerous other fields – it depends entirely on your local community!

3) Develop Your Entry and Expansion Strategy: The next step is defining your approach to addressing the ISV three pillars with the help of the ISV Engagement Committee. You need to answer questions about your plans for providing electricity (microgrids vs kiosks), education (technical, K-12, vocational), and entrepreneurship (jobs and revenue for both your organization and micro-entrepreneurs in the community).

4) Complete Three-Step Online Application: After creating your business plan and empowerment strategy, it is very important to put it down on paper. ISV has an online application process managed by the Project Development Committee, which covers the details on your community development vision and plans for providing electricity, education, and empowerment with the potential for regional scaling.

5) Start Fundraising: As a donor-funded program of the IEEE Foundation, our Funds Development Committee has to raise all the grant monies that we distribute. The sooner you submit an application and receive preliminary approval, the sooner we can secure funding for your project. We also highly encourage that you start raising matching funds using your application and empowerment plan! Some of our entrepreneurs have been able to leverage their standing as ISV Entrepreneurs to receive 10:1 matching funds.

6) Approval & Project Agreement: Final approval of all projects is by vote of our steering committee composed of the chairs of our 10 subcommittees. After approval, you will create a Project Agreement, which is a legal contract that describes your exact project sites, deliverables, schedule, staff, and matching contributions.

7) Deployment & Reporting: We provide our project funding in tranches of either $25,000 or $50,000 USD each time our Monitoring & Evaluation Committee receives and approves your progress reports with detailed metrics, photos, and description of project successes, challenges, and lessons learned.

8) Ongoing Support & Consulting: We have a dedicated staff of volunteers on our committees and Total Project Support Teams who will continue to support and advise you even after you complete your project agreement. As an ISV Entrepreneur, you become part of our Smart Village family, focused on open sharing of data, business technologies, education resources, lessons learned, and even business plans.

The best way to get started is to review the existing projects posted on our website, join us at the annual IEEE PES PowerAfrica Conference, and join some our committee meetings and training sessions designed to help you through the process of becoming an ISV Entrepreneur.

Volunteer Recruitment Coordinator

Responsibilities: Manage job postings; perform outreach to qualified candidates in IEEE and other organizations

Time Commitment: 2 hr/week for 1 year

Keywords: Human Resources; Volunteer Recruitment

Grant Application Writer

Responsibilities: Assist in writing grant applications for ISV projects; Assist in compiling sub-proposals from prospective ISV Entrepreneurs for use in funding applications

Time Commitment: 8 hr/week for 1 year

Keywords: Fundraising; Writing; Grant Applications

Education Committee Secretary

Responsibilities: Record, distribute minutes of the bi-weekly Education Committee online meetings focused on development of education projects and curricula

Time Commitment: 2 hr every 2 weeks for 1 year

Keywords: Education; Committee Secretary

Microgrid Simulation Analyst

Responsibilities: Evaluate new project designs; Run power flow simulations of proposed microgrids using OpenDSS, Xendee, GridLab-D, or similar software

Time Commitment: 10 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Technology; Project Review; Microgrids; Power System Simulation;

Social Media Manager

Responsibilities: Update ISV Social Media sites including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn

Time Commitment: 2 hr/week for 1 year

Keywords: Marketing; Writing; Social Media; Visual Art

Volunteer Screening Coordinator

Responsibilities: Review online applications submitted for committee positions; Direct candidates for orientation training

Time Commitment: 2 hr/week for 1 year

Keywords: Human Resources; Volunteer Recruitment

TV White Space Working Group Lead

Responsibilities: Lead consulting group for advising ISV Entrepreneurs and applicants about best applications, hardware, suppliers, installation methods of television white space technologies for internet and local intranet projects

Time Commitment: 4 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Internet & Connectivity; TVWS

Field Report Reviewer

Responsibilities: Review progress reports, quarterly reports, and tranche payment approval requests submitted by ISV Entrepreneurs; Provide summaries to ISV Steering Committee: Provide feedback to ISV Entrepreneurs.

Time Commitment: 4 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Monitoring & Evaluation; Project Management

Field Support TPST – Green Village Energy Nigeria

Responsibilities: Assist energy kiosk design, microgrid installation, and commissioning at 3 community centers and 35 schools in Papua New Guinea. Available as volunteer or intern position.

Time Commitment: 3 to 6 months on site

Keywords: Field Support; Papua New Guinea; Microgrids; Installation; Intern;

Business Strategy Reviewer

Responsibilities: Review and critique the sustainability and viability of business plans submitted by prospective ISV Entrepreneurs as part of online application process; Provide feedback and guidance for business plan improvements.

Time Commitment: 4 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Business Strategy; Project Review; Proposal Review

Technology Hardware Reviewer

Responsibilities: Evaluate new project designs, hardware selection, and controller compatibility

Time Commitment: 2 hr every 2 weeks for 1 year

Keywords: Technology; Project Review; Hardware Design; Component Evaluation; Microgrids

Grant Application Researcher

Responsibilities: Research potential grants which ISV may apply for using online searches and FoundationDirectory

Time Commitment: 8 hr/week for 1 year

Keywords: Fundraising; Research; Grant Applications

Video Editor

Responsibilities: Create and edit video content for YouTube, ISV website, and social media

Time Commitment: 12 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Marketing; Video; Visual Art;

Donor Outreach Working Group Lead

Responsibilities: Lead outreach to

Time Commitment: 10 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Fundraising; Donor Recruitment

Education Strategy Reviewer

Responsibilities: Review and critique the applicability and validity of education plans submitted by prospective ISV Entrepreneurs as part of online application process; Provide feedback and guidance to ISV applicants; Report results at Project Development & Education online meetings.

Time Commitment: 4 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Education; Project Review; Proposal Review

Press Release Developer

Responsibilities: Review project reports and create press releases publicizing items of interest; Coordinate with IEEE PR

Time Commitment: 4 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Marketing; Writing; Research

Technology Committee Secretary

Responsibilities: Record, distribute minutes of the bi-weekly technology Committee online meetings focused on development of microgrids, PAYGO systems, etc.

Time Commitment: 2 hr every 2 weeks for 1 year

Keywords: Technology; Committee Secretary

Women’s Empowerment Working Group Lead

Responsibilities: Organize a team to identify, sort, develop, and assemble training resources in women’s empowerment; Assist ISV Entrepreneurs in implementing women’s empowerment programs in Africa, India, Asia, Americas

Time Commitment: 2 hr every 2 weeks for 1 year

Keywords: Education; Research; Women’s Empowerment

Volunteer Orientation Coordinator

Responsibilities: Provide brief orientation training to new volunteers by email, phone; Assist development of pre-recorded orientation videos and training

Time Commitment: 10 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Human Resources; Volunteer Recruitment

Field Support TPST – Green Village Energy Nigeria

Responsibilities: Assist with on-the-ground research on expansion opportunities for a successful solar microgrid ISV Entrepreneur in Rivers State, Nigeria.

Time Commitment: 3 to 6 months on site

Keywords: Field Support; Nigeria; Microgrids; Research; Intern;

Website Updates Manager

Responsibilities: Update ISV website with new materials, announcements, webpages. WordPress experience required.

Time Commitment: 12 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Marketing; Web Development; WordPress

Project Development Committee Secretary

Responsibilities: Record, distribute minutes of the monthly Project Development Committee online meetings.

Time Commitment: 2 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Project Development; Committee Secretary

Crowdfunding Working Group Lead

Responsibilities: Organize crowdfunding programs in collaboration with IEEE Foundation

Time Commitment: 4 hr/week for 1 year

Keywords: Fundraising; Donor Recruitment

Project Expense Manager

Responsibilities: Track specific project costs; Compare budget line items; Communicate variances to Steering Committee.

Time Commitment: 10hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Finance; Budgets; Project Management

Marketing Committee Secretary

Responsibilities: Record, distribute minutes of the monthly Marketing Committee online meetings.

Time Commitment: 2 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Marketing; Committee Secretary

IEEE OU Outreach Working Group Lead

Responsibilities: Lead outreach to IEEE Organization Units for funding requests; Establish relationships with IEEE Society financial committees;

Time Commitment: 10 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Fundraising; IEEE Societies

Microgrid Training Working Group Lead

Responsibilities: Organize a team to identify, sort, develop, and assemble training resources in microgrid design, installation, commissioning; Assist ISV Entrepreneurs in receiving appropriate technical training

Time Commitment: 2 hr every 2 weeks for 1 year

Keywords: Education; Microgrids;

Volunteer Recognition Coordinator

Responsibilities: Assist development of methods for recognition of volunteer contribution of ISV

Time Commitment: 4 hr/month for 1 year

Keywords: Human Resources; Volunteer Recognition